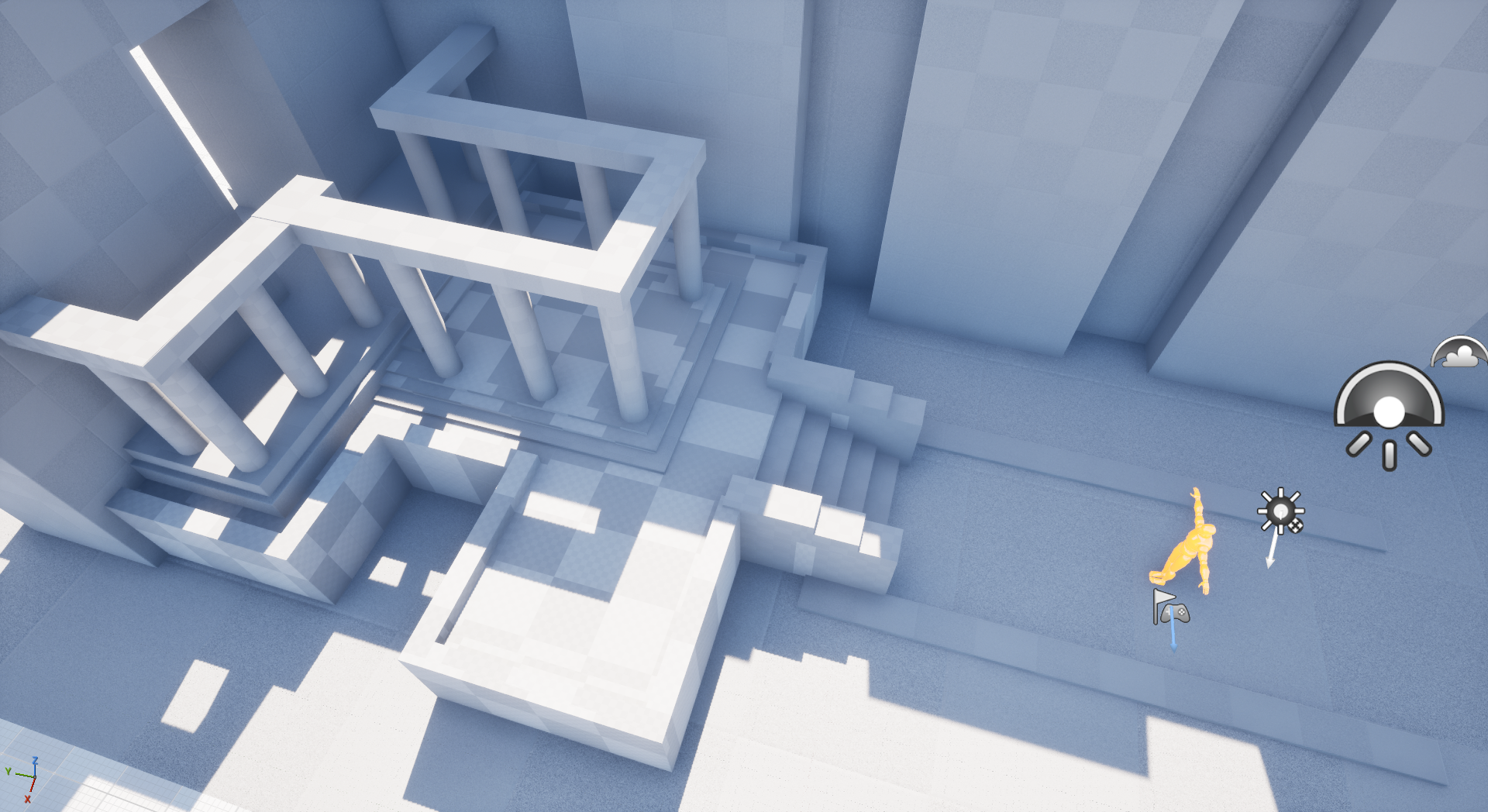

Walking up stairs

The BRAWL² Tournament Challenge has been announced!

It starts May 12, and ends Oct 17. Let's see what you got!

https://polycount.com/discussion/237047/the-brawl²-tournament

It starts May 12, and ends Oct 17. Let's see what you got!

https://polycount.com/discussion/237047/the-brawl²-tournament

Best Of

Re: The Bi-Monthly Environment Art Challenge | November - December (99)

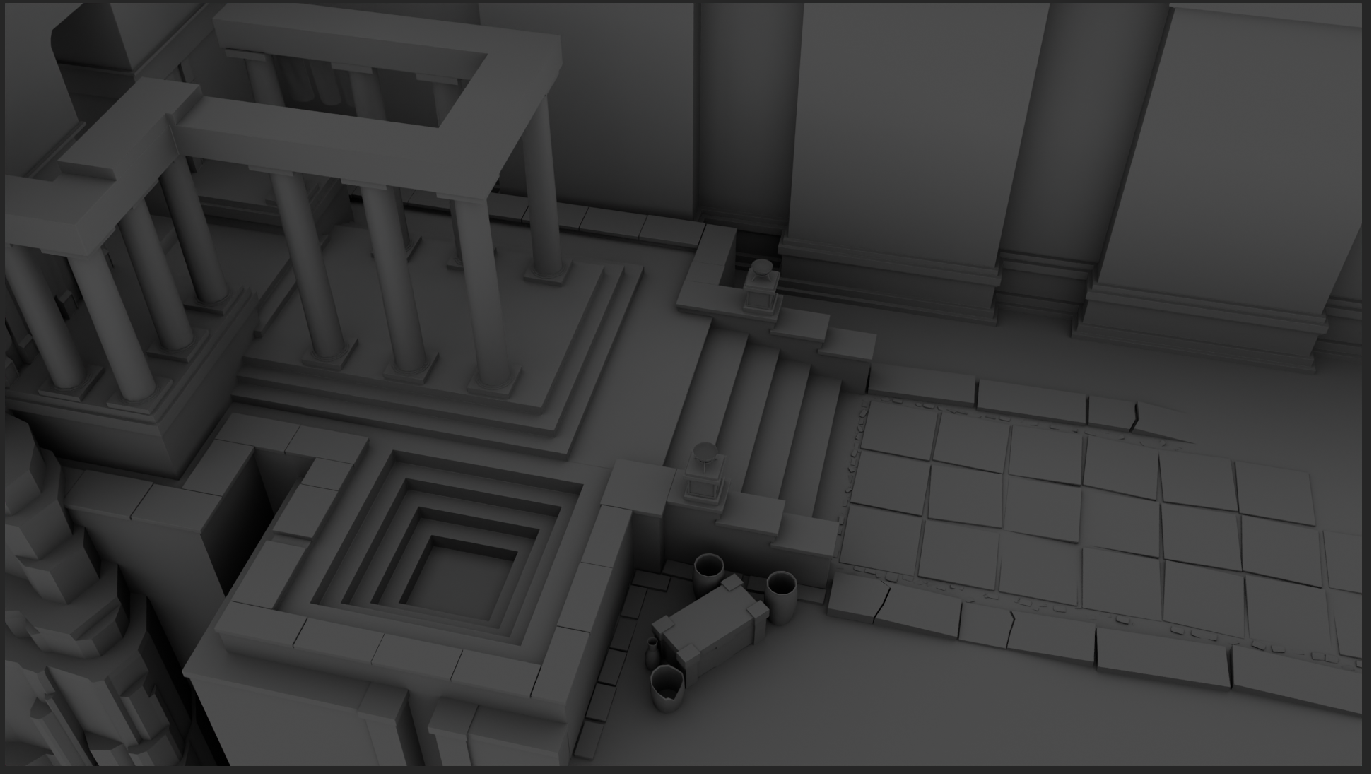

started on this one a while ago but didn't have much time to finish, hope to do so soon (not 6 months later)

3 ·

Re: The Bi-Monthly Environment Art Challenge | November - December (99)

Hey everyone!

Wanted to start out by saying what fantastic work everyone has done on this challenge. It's been incredible to see not just the progress being made but the process breakdowns that are so beneficial for more junior and senior artists alike. There are definitely some techniques I've picked up that I hope to try sometime in the future.

Hope you all had a stellar holiday break as well with great company and wonderful food. With the new year upon us it's also time to announce that the 100th edition of the Bi-Monthly Environment Art Challenge has officially begun!

Pinkfox

Pinkfox

3 ·

Re: The Bi-Monthly Environment Art Challenge | January - February (100)

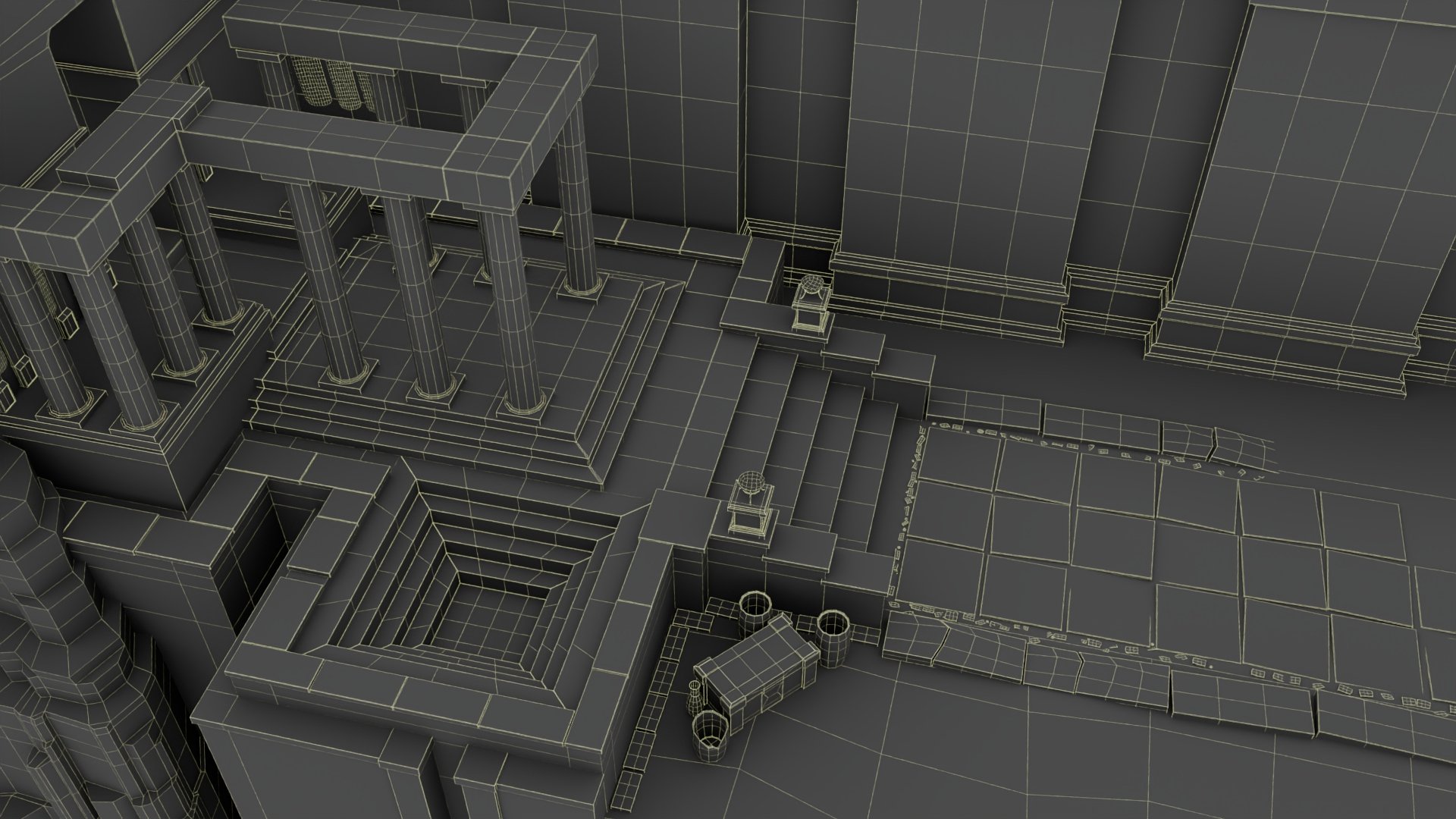

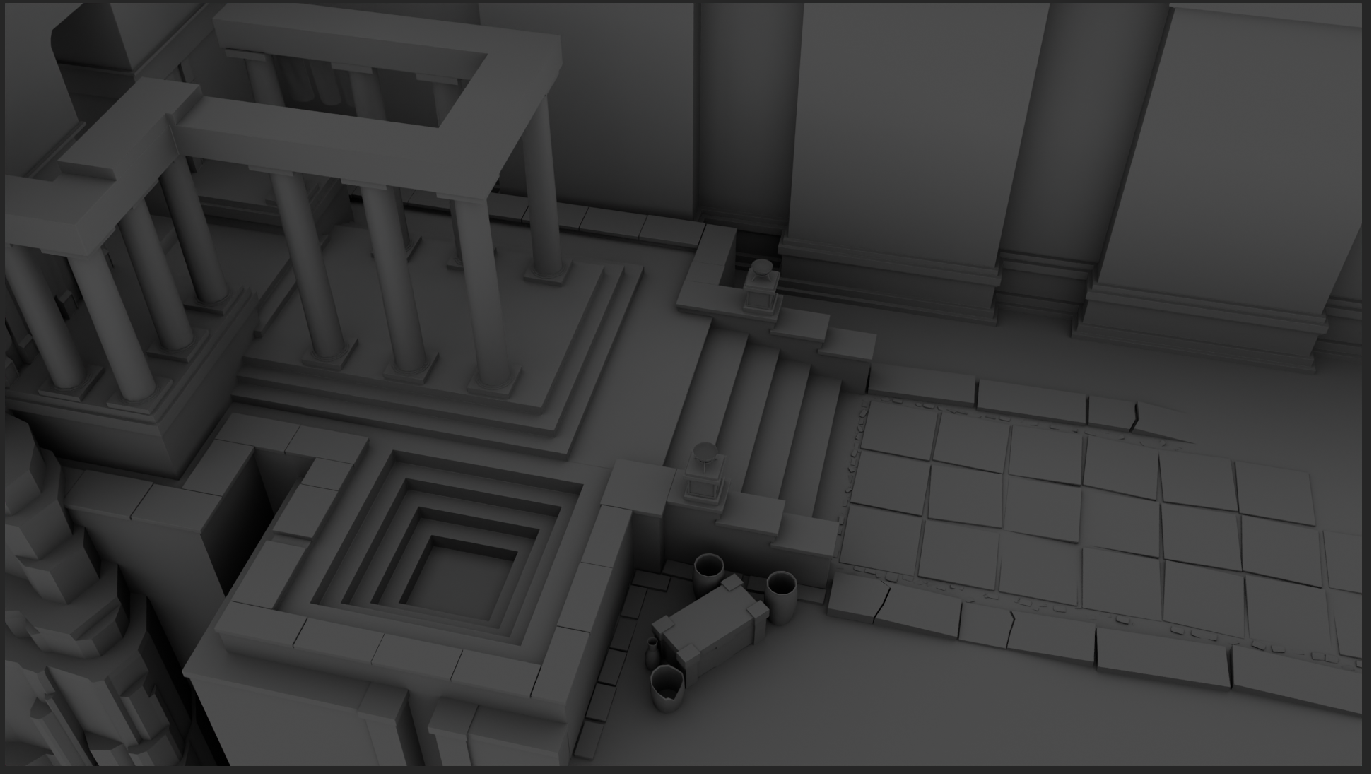

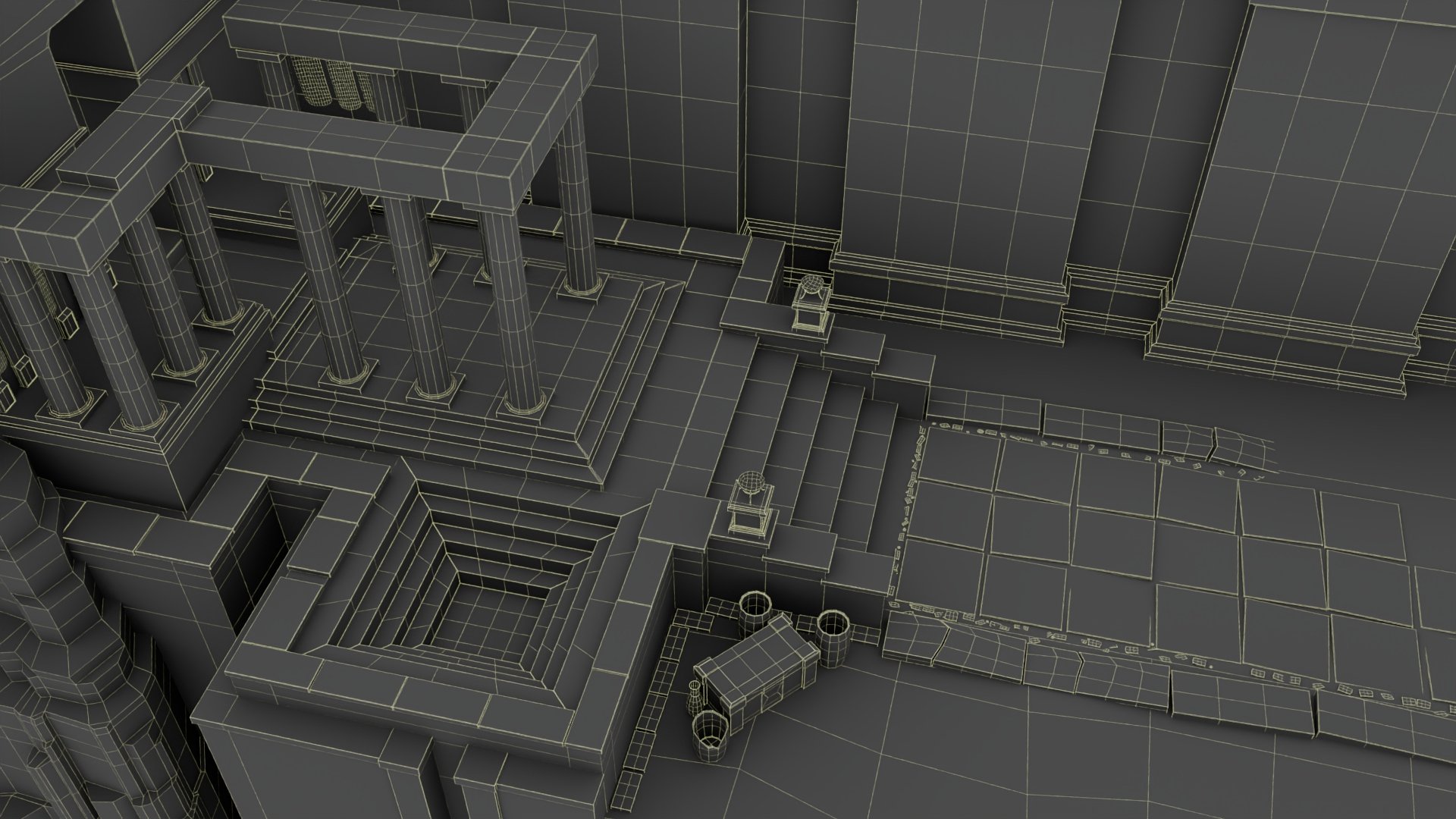

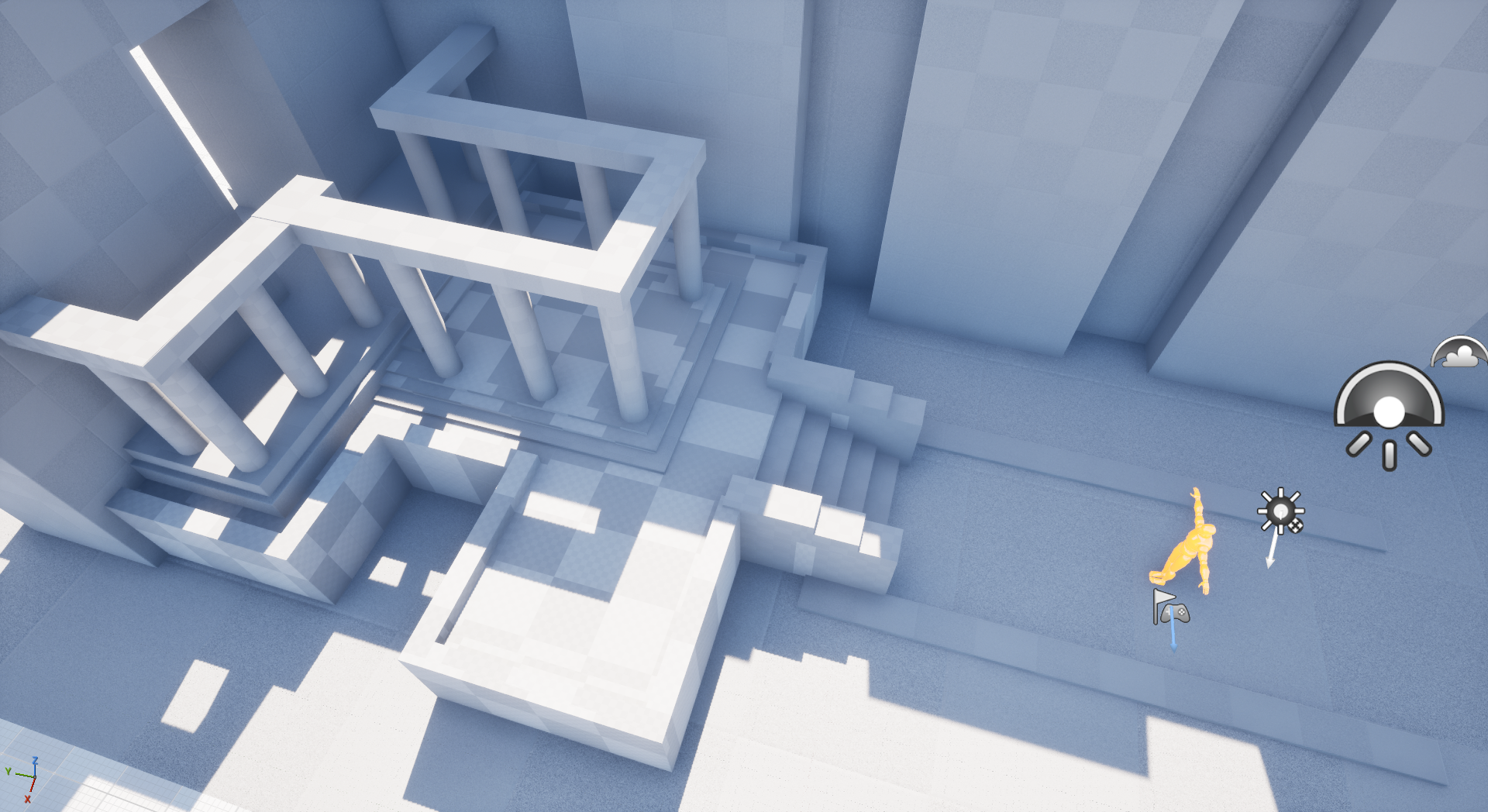

Managed to get the general base down for the environment and I wanna tackle the remaining parts in ZBrush. It's come out to around 40k polys with even edgeflow and support loops on most assets which could be dropped significantly if required. Considering however that higher detail will be baked and that modern specs allow for far higher poly's I think it'll be okay. Furthermore I plan to bake the scattered rocks and tiles onto the ground plane so that will lower the total poly count by 11k.

4 ·

Re: Azimuth Cold - FPS game visual prototype

I added an active reload system, similar to Gears of War, where while reloading you have a progress bar, and if you hit "R" at the right time, it will speed up the reload, if you miss, it will slow it down. Also, there are 2 variants: Tactical reload - when player have bullet in the barrel and Emergency variant when not.

Sigmatron

Sigmatron

4 ·

Re: The Bi-Monthly Environment Art Challenge | January - February (100)

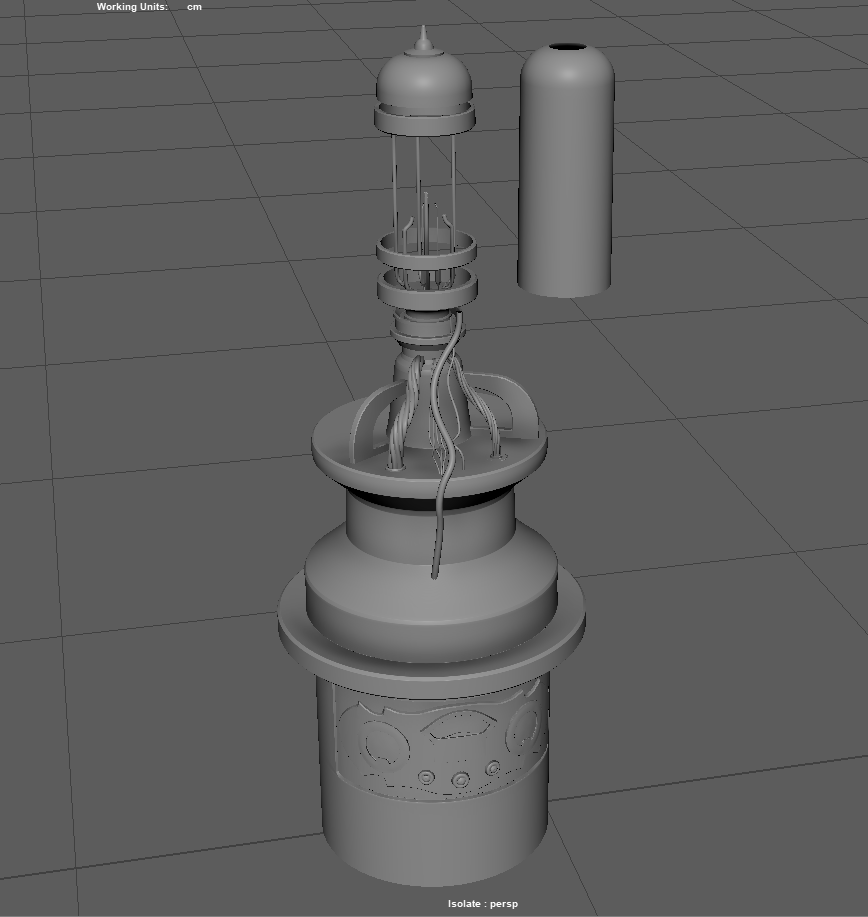

Hello guys, I don't use game engines so I decided to make this in Blender, I haven't touched anything 3D in almost 2-3 years with my last time trying to do this bi-monthly challenge. This is after a week of progress (obviously still not finished), I don't know if I should make it as stylized as the concept art or I can make it however I want. But this is my first time using Substance Painter so I'm not that familiar enough with the software to try a stylized approach.

5 ·

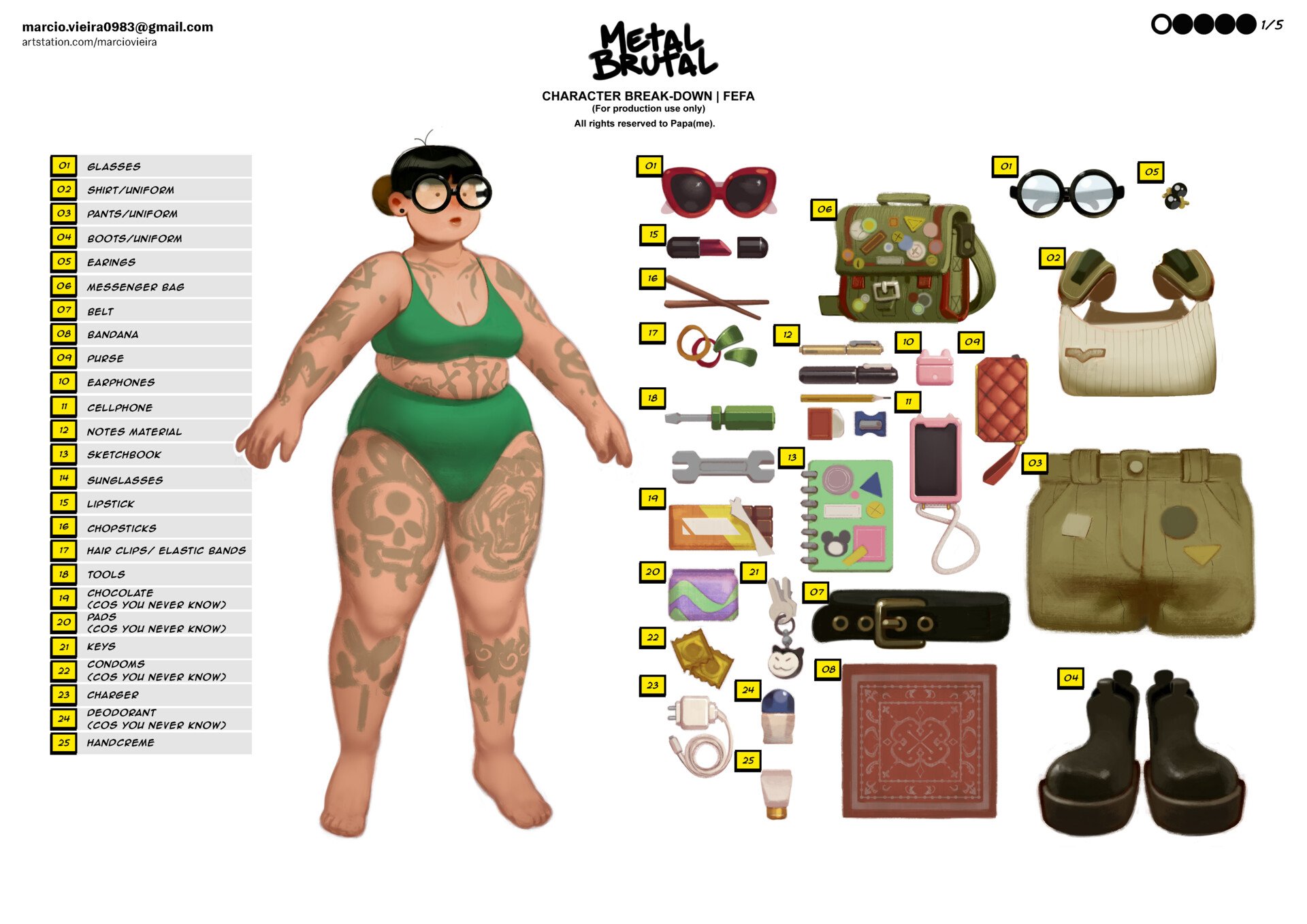

Re: [WIP] - Game Ready Stylized 3D Character

I will add the bag yeah, I started modelling it but there's another concept art that confuses me on how the bag should look and work in 3d.

As for the area under the belt I tried to look for real life references but it might make sense to add more volume re-looking at the concept art. Thanks for the nice words and the feedback much appreciated!

As for the area under the belt I tried to look for real life references but it might make sense to add more volume re-looking at the concept art. Thanks for the nice words and the feedback much appreciated!

egeguncu

egeguncu

3 ·

Re: The Bi-Monthly Environment Art Challenge | January - February (100)

Ey this is my first time entering these challenges. I'll look for any feedback during my progress (●'◡'●). This is my first approximation for the blocking, it's not done yet since they are more little elements absent, and I wanted to get scale feeling first.

As an extra idea, I want to add some vivid element involving the pond. By the time, I sketch a little cascade path. I will explore a couple of ideas that aren't too flashy, since I don't want the pond element to fight the visual attraction of the main exit structure. ヾ(@⌒ー⌒@)ノ

As an extra idea, I want to add some vivid element involving the pond. By the time, I sketch a little cascade path. I will explore a couple of ideas that aren't too flashy, since I don't want the pond element to fight the visual attraction of the main exit structure. ヾ(@⌒ー⌒@)ノ

Rudy_Yair

Rudy_Yair

8 ·

Live 3d embeds!

This is pretty neat, you can embed a live real-time 3D viewer here on Polycount, using Sketchfab!

model

Instructions and details here:

https://polycount.com/discussion/160022/sketchfab-integration

Looking forward to seeing your models in some live embeds!

model

Instructions and details here:

https://polycount.com/discussion/160022/sketchfab-integration

Looking forward to seeing your models in some live embeds!

Eric Chadwick

Eric Chadwick

4 ·

Re: Don't Use AI for Replies

It blows my mind that no tool exists for AI-automated retopology.zetheros said:yea, disclosure that AI was used sounds good. As for the rest, I can really only speak to what I see and do on a daily basis. After a day's work of making 3d assets for my job, I spend an additional hour or more making art on the side, and this is what I've done consistently for the past 3 years. During that time I have yet to find a genuinely compelling reason to use generative AI.

People have completely jumped ahead into making shitty full AI-generated models which are ugly and completely unusable for anything, but nothing for retopology

Zack Maxwell

Zack Maxwell

3 ·